by Emily Rinaman, Technical Services Manager

In these parts, once the frenzy of the Christmas holiday has died down and the sluggishness of winter kicks into high gear, people start looking forward to the next major event on the calendar – the return of the Paczki. When you see these on the grocery store shelves, you know the season of Lent is near. Fat Tuesday, the day before Ash Wednesday, is celebrated in a wide variety of ways in different parts of the world, from somberness to outright celebrations, the largest being Carnival.

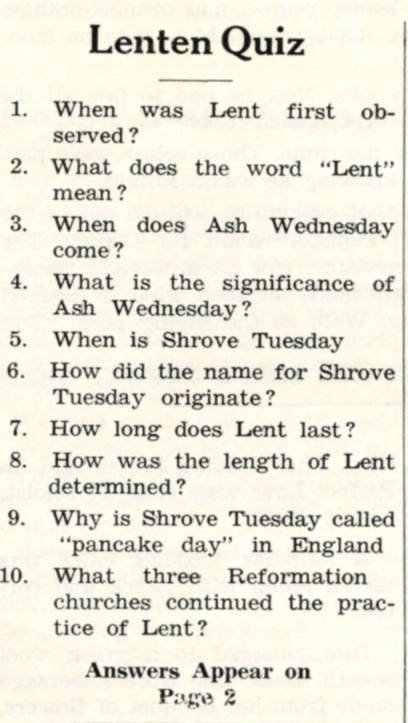

Carnival, like most other Christian holidays, has pagan roots and is deeply intertwined with symbolism, music, and the seasons (see trivia questions taken from Tiffin University’s TYSTENAC, March 1967).

A true Carnival (Americans very loosely use the word to describe some public parties, such as a fall carnival) is a public celebration, like a parade, ball or street party.

Street parties were particularly popular in the United States in the middle of the 20th century, but didn’t necessarily celebrate the coming of Lent and longer days of sunlight.

Taken from the Green Springs Ohio Centennial, which has been digitized onto the Seneca County Digital Library, the caption for this photo states “scene of corn festival, 1920.” It appears to be set up in the downtown area, an example of a street carnival, which were popular in the early 20th century.

The Elks Lodge in Tiffin put on a street carnival for several years in the early 1900s as a way to raise funds for a new lodge building. Their street carnivals, which actually took place on the streets of Tiffin (Washington Street from Perry St. to Madison Street), brought in a Ferris wheel and a merry-go-round. They included “side shows” and “games of chance.” The last Elks street carnival was held in 1912 before the major flood in the spring of 1913 put a hiatus on them.

In fact, street carnivals were so popular during this time period that the students at Hopewell-Loudon performed a play in 1940 using a street carnival as its main scene. Traditionally, Carnival has contributed extensively to the theater. In Trinidad and Tobago, they actually incorporate musical corporations into their carnival celebrations.

While Europeans are the ones responsible for bringing the old-world carnival traditions to the Americas, the Native Americans held their own carnival-like celebrations during the dead of winter. In Ohio, early settlers discovered that Native Americans, particularly the Senecas and Cayahogas, from this area celebrated a dog dance. Some of the details of these mid-winter ceremonies are gruesome but what’s notable is that, like many of the natives’ ceremonies, this one involved music. “The object was to keep in time and move with the music.” (as they danced around the fire)

More modern American carnivals were simply an excuse to get together as a community for a big party, mirroring the Medevil purpose of having an outlet from daily stressor. In 1877, a carnival was held at the fairgrounds, which invited in a balloonist and offered horse races, sack races, wheelbarrow races, pig races and slippery pole climbing.

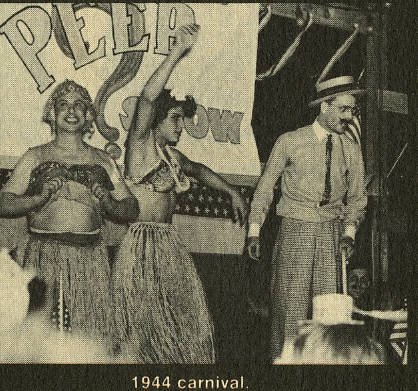

Performers look like they are having fun at a 1944 carnival hosted by National Machinery for its employees and their guests to boost morale while fellow employees and family served overseas during World War II.

Carnivals were popular among campuses and were often hosted by fraternities and sororities. The annual Girls Reserve group at Columbian High School held a yearly Carnival in February in the 1930s, but probably more to distract themselves from the hard times of the Depression Era than anything else. At their “miniature carnivals,” they would play cards, bingo, and other games. Originally, the Girls Reserve program was begun to garner enthusiasm for war efforts. After World War I, the popularity of this group skyrocketed.

At Tiffin University, in April 1947, the Kappa Delta Phi Sorority sponsored a carnival in the Social Hall. Just two years after World War II, this carnival more than likely served the same purpose. It enticed “fun seekers” to activities like darts, fortune-telling, “fishing,” and candy-bending.

National Machinery had many male employees who served in World War II and in order to keep the morale up for those back home in the states, they held a carnival in June 1944 featuring “Whiskers, the Bearded Lady,” “Ox-O the Strong Man,” “Bones the Living Skeleton,” plus a magician and wild animal show. Over 400 guests were entertained by live music from the Don Jacobs’ Orchestra of Fostoria and an area of the room was arranged for card playing.

Works cited:

Third Annual Heritage Festival, 1817-1981. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/27465/rec/1

History of Seneca County from the close of the Revolutionary War to July 1880. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/17560/rec/2

Yearbook Scarlet and Gray 1940. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/48462/rec/1

National Servicemen’s News Bulletin, Vol. 1, Number 9. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/64293/rec/4

Yearbook Columbian Blue and Gold 1938. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/2967/rec/1

The What, How and Who of It: an Ohio Community in 1856-1880 by Howard Smith. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/16074/rec/1

Tystanac May, 1947. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/45622/rec/2

National Machinery 100 Years. Seneca County Digital Library.

“The Origins and History of Carnival.” Carnivaland. https://www.carnivaland.net/origin-history-carnival-worlds-oldest-party/

Editors of Encylopedia Britannica. “Carnival: Pre-Lent Festival.” Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Carnival-pre-Lent-festival

“A Moment in Our History: Touching the Lives of future generations: From Girl Reserves and Y-Teens to Girls’ Summit.” April 28, 2020. https://www.ywcaoahu.org/ywca-oahu-120/2020/4/28/a-moment-in-our-history-touching-the-lives-of-future-generations-from-girl-reserves-and-y-teens-to-girls-summit

Grinberg, Emanuella. “Mardi Gras: The Most You’ll Have with a History Lesson.” Feb. 21, 2020. CNN Travel. https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/mardi-gras-fat-tuesday-history/index.html