By Emily Rinaman, Technical Services Manager

The title of this month’s blog comes from a poem written by Judy Singer, a student from Alliance High School in the late 1950s (to read the poem in it’s entirety, visit the Seneca County Digital Library).

As the years pass, humans rely more and more on technology to do the jobs that once required physical and mental effort. This includes setting the time when Daylight Saving Time begins and ends each spring and autumn. Now, smart watches, cell phones and other electronic devices are programmed to automatically switch the hour so that when you wake up the next morning, it’s as if magic happened overnight. Unless one still owns battery operated clocks, the mad dash to change the hands on them around the house before falling asleep on the nights we lose or gain an hour has become a thing of the past. Even then, however, correcting a clock’s time was still easier than when clocks and watches were in their height of glory.

The original clock tower of the 1884 Seneca County Courthouse, which remained until 1944.

In ancient times several rudimentary tools were used by cultures to keep track of the time, including sun dials, candle clocks, or even simply watching the shape of shadows change throughout the day. As society became more complex, people looked for ways to more accurately tell the time. It wasn’t until the 1300s-1500s when the more modern idea of a clock emerged.

Towards the end of the Middle Ages, many churches and other buildings throughout Europe had installed a clock tower with mechanical clocks, mechanical meaning the clocks had to be re-wound (or, in other words, re-set) daily. The town clock then helped its residents keep consistent routines and function as a whole. But there was also a more “personal” reason—prayers were said at specific times and hearing the bell toll signaled prayer time. This is how clocks received their name – the English version derives from the Latin word for bell, “clocca.”

Tiffin once had a very renowned clock tower for Tiffinites to keep track on the time. When the original Seneca County Courthouse was built in 1884, this original clock would tell Tiffinites the time until 1944 when it was replaced (the cast iron tower had deteriorated). Interestingly, this new clock would prove to be testy itself. Amy Madden wrote an article called “When the Clock Strikes Twelve” in the Yearbook Columbian Blue and Gold 1988, recapping a major New Year’s Eve celebration on the courthouse lawn. The clock apparently hadn’t been keeping the correct time for almost ten years, and it was reset just in time to ring in the new year, 1989. Another clock tower was supposed to have been built in the Tiffin Union School, but was never completed due to insufficient funds.

West Lodi residents Isaac and Christina Scothorn Tompkins display their grandfather clock (to the left of the standing couple), a prized possession.

Many cities in both Europe and the United States held at least one clock tower because clocks were once very expensive to own. It wasn’t until 1581 when Galileo discovered that pendulums could be used inside clocks that they became a household commodity. An image of a chiming grandfather clock might come to mind when many of us think of our childhood visits to our grandparents’ houses. While they still are somewhat of a statement piece, historically they were a sign of wealth. Through the 1700s, only noble and upper class families could afford them, but this gradually changed as time went on. However, they never completely stopped serving as a sign of well-being. West Lodi residents Isaac and Christina Scothorn Tompkins dragged their prized possessions onto the front porch of their home for a photograph, including a grandfather clock (see photo). If you look closely, you will see its shiny clockface to the left of the woman standing on the porch.

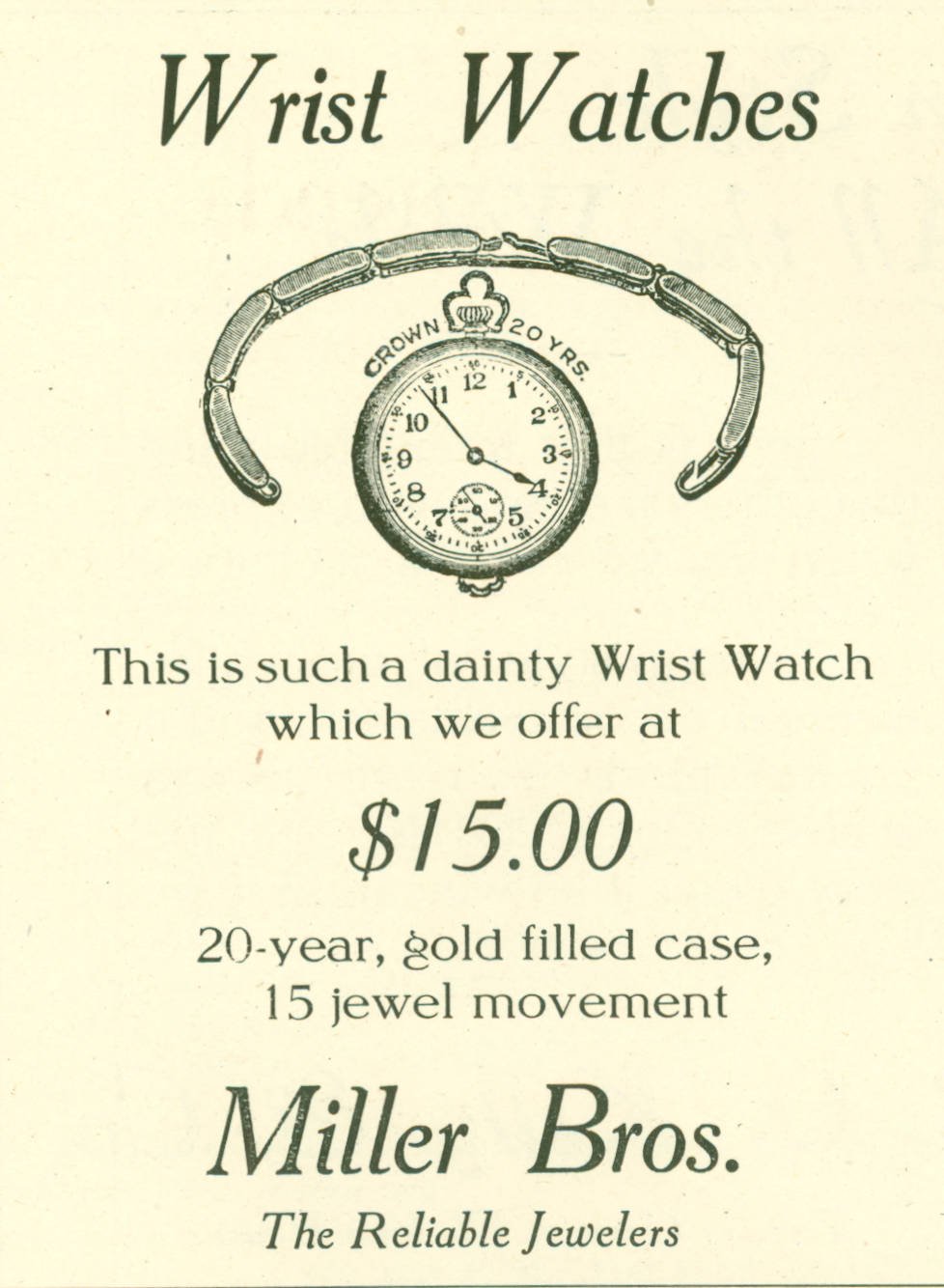

An ad in the Tiffinian, Columbian’s long-ago newspaper.

By the turn of the century, jewelry makers had figured out how to create wearable clocks--pocket watches became all the rage for men and wrist watches were preferred by women, as they were seen as a functional bracelet. It wasn’t until World War I when soldiers in the trenches wore watches to aid in their battle strategies that civilian men began sporting wrist watches alongside the females.

But because clocks and watches had to constantly be re-wound, the innovations for instruments with more accurate time-keeping kept emerging. Today, our smart devices are what’s called “atomic clocks” because they are calibrated by International Atomic Time. While once individual municipalities could keep their own times within their small circles, the entire world is now designed into a modern time-keeping system. The old adage, “excuse me, sir, do you have the time?” is hardly spoken. The ticking of a clock is hardly heard. Now, you can just ask Alexa or Siri!

Works cited:

Andrewes, William J.H. “A Chronicle of Timekeeping.” Scientific American. February 1, 2006. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/a-chronicle-of-timekeeping-2006-02/

Barnes, Myron. Between the Eighties. https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/65253/rec/10

“A Brief History of the Grandfather Clock.” https://www.thewellmadeclock.com/brief-history-grandfather-clock/ “

“History of Men’s Watches, 1900s to 1960s.” https://vintagedancer.com/vintage/history-mens-watches/

Madden, Amy. “When the Clock Strikes Twelve.” Yearbook Columbian Blue and Gold 1988, https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/12046/rec/1

McFadden, Christopher. “The Very Long and Fascinating History of Clocks.” April 13, 2019. https://interestingengineering.com/the-very-long-and-fascinating-history-of-clocks

Monroe Street School Centennial. https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/35483/rec/1

Seneca County Digital Library. https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/search

Seneca County Ohio History Families. https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/28319/rec/7

Singer, Judy. “Music.” Young America Sings National High School Poetry Association 1958-1959. https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/50751/rec/1

Smith, Howard. The What, How and Who of It: an Ohio Community in 1856-1880. https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/15811/rec/1